Treasures Worth Saving: An Interview with Christopher Payne

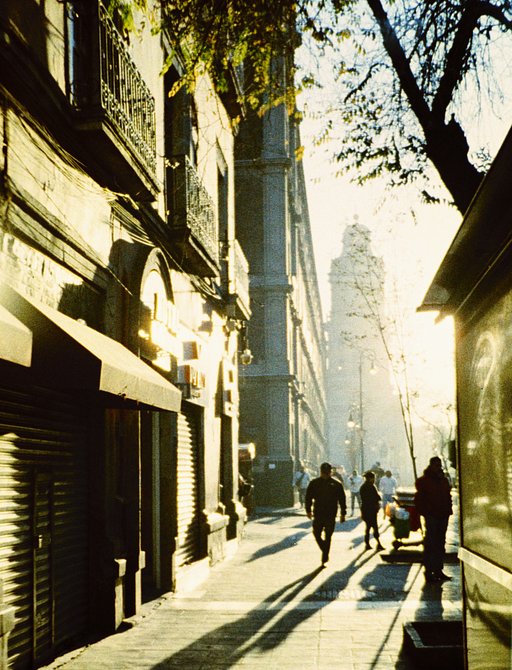

2 21 Share TweetArchitectural photographer Christopher Payne documents America’s industrial heritage with his large format images. For his project “Asylum,” he visited 70 abandoned psychiatric hospitals across to country between 2002 and 2008.

Using photography as a medium to explore the concept of construction and deconstruction, he tries to eternalize fading architectural treasures. In this interview, he tells us about the purpose of his work and the challenges that the stigma of mental health institutions posed for him.

With a background in architecture, how did you get into photography in the first place?

I became interested in photography while I was working as an architect. It happened almost out of necessity. My first book, New York’s Forgotten Substations: The Power Behind the Subway, was originally envisioned as a book of drawings, based on detailed sketches I was making of the giant electrical machines in the substations. I rarely had time to finish the sketches on site, so I took pictures to help me complete them later at home. Over time these snapshots became more complex, and I found myself enjoying the preparation and taking of the pictures more than I did the drawings. It was a gradual process, but once the book was finished I knew I had found my calling.

How does your background in architecture influence your practice as a photographer? Not just in terms of subject but in your approach?

I still think like an architect and use photography to show how things are designed, assembled, and how they work. Sometimes it’s a process of reconstruction, as with Asylum, where I tried to recreate a whole from parts that survived here and there, across the country. With my latest book, Making Steinway, about the famous Steinway & Sons piano factory in Astoria, Queens, I took the opposite approach. Here, my photographs are a deconstruction of something we all know and love as a whole into its unseen constituent parts, and a glimpse into the skilled labor required to make them. My architectural training also comes in handy because it helps me previsualize a shot, much like making a sketch on paper. In many ways, I feel like I’m grappling with the same questions and trying to tell the same story; I’ve just traded one medium for another.

What is the fascination about abandoned places, ruins and documenting the industrial heritage of the US for you? What significance do your subjects have from an architectural, photographic and societal point of view?

My interest in abandonment is a by-product of the subjects I am most drawn to: industrial processes and antiquated infrastructure, and the old buildings that house them. Many of these places were designed for a specific purpose at a particular time, so the architecture is unique. For instance, almost all 19th century hospitals were modeled on the “Kirkbride” plan. From the sky, this arrangement looked like a row of birds in flight. The Kirkbride plan was an American invention that gave rise to some of the largest buildings of their time. It was also an acknowledgment, manifested in a new building typology, of mental illness as a disease, and its unique layout represented an attempt to impose a system of classification and control. The asylums bestowed legitimacy on the nascent profession of psychiatry, which was not yet part of mainstream medicine. So in a sense, the history of psychiatry in the Unites States is the history of the state hospitals, and that’s what makes the architecture so significant.

How did you get the idea for Asylum?

I actually came upon the asylums by chance. I had just finished the Substations book and needed a new project to fill the creative void. A friend, who knew of my interest in industrial architecture and abandoned infrastructure, suggested state hospitals. The first place I visited was Pilgrim State Hospital, about an hour from the New York City. I didn’t realize it was the largest psychiatric hospital ever built, so seeing its empty streets and rows of shuttered buildings left a strong impression on me that day—and a desire to learn more. In the weeks following, I discovered more hospitals in the area, similar to Pilgrim, and things took off from there.

What surprised you most about the hospitals you visited?

What surprised me most were the similar histories of all the state hospitals. Whether they were located in Maine, Alabama, or Iowa, they were essentially the same, and had once operated along the same lines as self sufficient communities, where almost everything of necessity was produced on site: food, water, power, and even clothing and shoes.

Why did you choose large format for this project?

For almost all of my personal work I still shoot film with a 4×5 view camera, because this is what I learned on, and it’s perfect for architecture and correcting perspective. I also like the view camera because of its meditative, deliberate process, and I love getting lost in the detail of a large negative. I’ve been using the same camera and lenses for over fifteen years, and I’m grateful for its simplicity every time I have to update my expensive digital cameras.

Tell us more about the setup at the scene.

In terms of setup for Asylum, I tried to keep things simple and relied on natural light wherever possible. Typically, to get the creative juices flowing, I began with the same shot at each hospital: the iconic straight on view looking down a patient ward. The proportions of this space, where the width of the hall is slightly greater than its height, fit perfectly into the 4×5 frame.

What were your biggest challenges during this project?

Contrary to what you might think, getting access to the hospitals was the easy part. Once I received permission from a few states, other states followed suit. Eventually I visited seventy hospitals across the country, many of which held enough history and visual material to be projects of their own. Working with film forced me to make some tough editing decisions because I couldn’t photograph everything that caught my eye (like one can with digital). With that in mind, the biggest challenge was deciding what not to shoot.

Despite decaying facades and crumbling interiors, some of the rooms look like the people inhabiting them had just left. There is a sense of vividness in the photographs. How did you achieve this?

For every room that was frozen in time, there were dozens that were empty or decayed beyond recognition. Finding shots that looked as if the occupants had just left took a lot of patience and persistence, and much of my time was spent going through the buildings, checking every room and opening every door. The inverse of this trial and error approach, and the one that I preferred, was having a guide show me around, a veteran employee who knew all the buildings and which spaces were still intact and worth a picture. Through their recollections, the vacant buildings and campuses would come alive. Hearing their stories always made me sad because many of the employees had grown up on the grounds, and these hospitals were their homes.

In our society, there is a certain stigma surrounding mental health issues. Has that influenced your project in any way as, say, compared to the documentation of the power stations behind the New York City subway system?

Unfortunately, the stigma attached to mental illness has been passed on to the hospital buildings. As vestiges of a less enlightened era, the old asylums do not elicit the same nostalgia as other historic structures. Until public perception and apathy changes, these buildings will continue to fall victim to the wrecker’s ball. So this lends an urgency to the work I do, because I never know when a building will be demolished. Most of the images in my book no longer exist.

More than just documenting the decay and creating a final record of these buildings, you provide an insight into the lives of those who spent their days in these institutions. Were there any aspects you were trying to highlight with your photographs?

I hope my audience will see these institutions in a more objective light and realize they were more than just “snake pits”; they were once thriving self-sufficient communities where thousands of people lived, worked, and died, and they played a vital role in American society, for better or worse, for more than a century. Before they became objects of derision, the asylums were sources of great civic pride, built with noble intentions by leading architects and physicians, who envisioned the asylums as places of refuge, therapy, and healing. I hope people will realize these architectural treasures are worth saving instead of tearing down, even if they are negative symbols of a less enlightened era. Buildings of such grandeur, detail, and beauty will never be seen again.

When you started the project, did you do any research on the people working in and inhabiting the buildings? Do you feel connected to them in some way? Do you believe in the presence of their souls?

I researched important figures in the mental health movement to provide context for my pictures, but not the patients or workers themselves. The presence of their souls was evident in the empty spaces and artifacts left behind, but not in a creepy or eerie way. Given my love of architecture, I developed a strong connection with the buildings. I spent hours inside them, working alone and undisturbed. I couldn’t help but feel a certain intimacy with them, and a strong sense of protectorship and responsibility as, perhaps, their final documenter.

Asylum will be on display from February 11 to March 26, 2016 at Benrubi Gallery in New York. The Opening Reception will be held on Thursday, February 11, 2016 from 6 to 8 pm. To see more of Christopher Payne’s work, visit his website.

In case you missed it, here is the first feature on Christopher Payne on the Magazine.

written by Teresa Sutter on 2016-02-09 #people #places #interview #location #asylum #industrial-heritage #large-format-photography #christopher-payne #substations

2 Comments