"School Memories: The Loss in Danwon High" by Argus Paul Estabrook

1 9 Share TweetTo talk about the loss of a loved one and allow a complete stranger to photograph the grief and pain that come with it is never easy. Bound by mutual trust and respect, South Korea-based photographer Argus Paul Estabrook and the subjects of his poignant series School Memories: The Loss in Danwon High found a common ground: to preserve a memory.

In this interview, Estabrook opens up about his moving and powerful photographs which capture the aftermath of a tragedy that claimed the lives of students and teachers from Danwon High School and how the families of the departed deal with losing their loved ones for a second time.

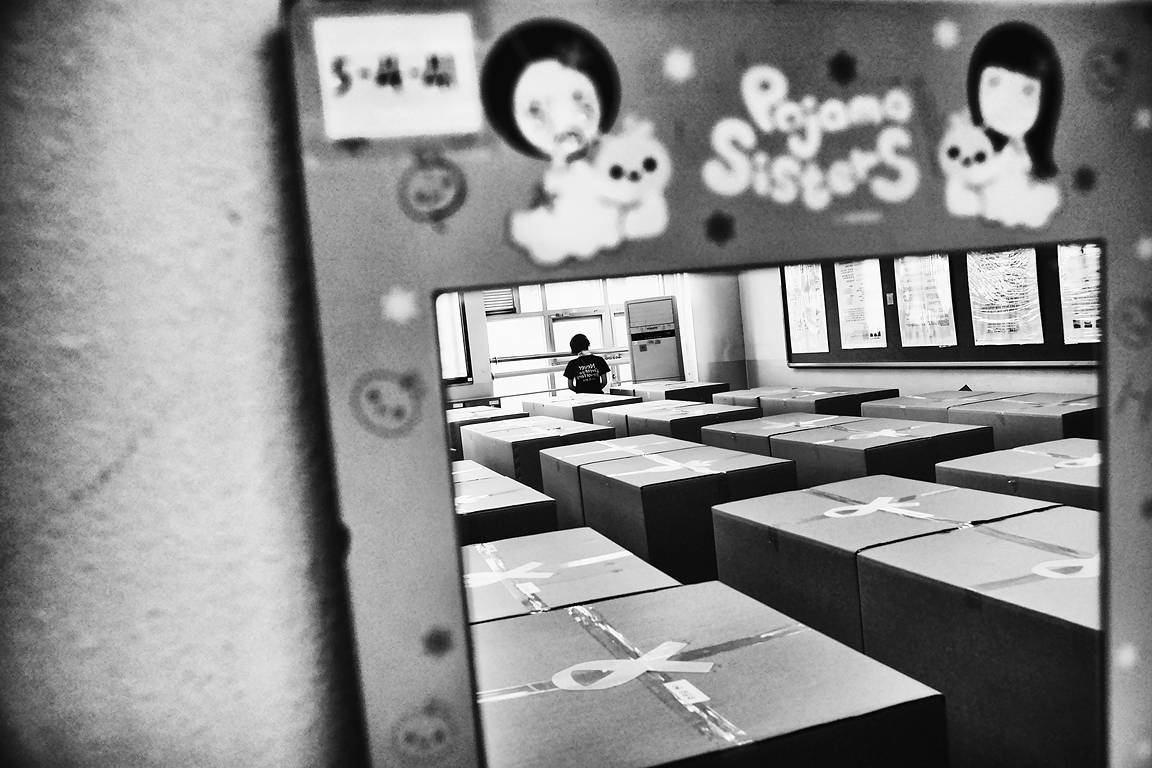

“Ten classrooms at Danwon High School were spontaneously transformed into memorial sites during the Sewol Ferry Tragedy on April 16, 2014, when the lives of 250 students and 12 teachers (nearly its entire second year class) were lost off the coast of Donggeochado, South Korea. Overnight these classrooms were covered in their own sea of photographs and personal letters addressed to the departed. Blackboards became overwritten with confessionals while items such as calendars and class schedules remained untouched on the walls. From this origin of loss, these classrooms emerged as sacred spaces, repositories of memory.

“Amidst debate of what should be done to preserve the memorials, a controversial attempt to forcibly clear out and remodel the classrooms was made almost immediately after the second year anniversary of the tragedy. For several days, family members occupied the school grounds until an extension was granted to access the classrooms for a few more weekends.

“In August of 2016, the school resumed renovations and removal of all memorial items. While both government and school officials have said that they will oversee storage and the construction of a new memorial off site in two year’s time, specific details have been scarce, leaving families of the victims distrustful. Some say they will continue to protest so the lessons of Sewol will never be forgotten. Others believe proper preservation can’t be achieved once the classrooms are stripped away anew.

“Powerless against the forces that be, these families say they’re losing their children and loved ones for a second time.”

- Argus Paul Estrabrook, School Memories: The Loss in Danwon High

Hello Paul and thank you for your time. Your photo series School Memories: The Loss in Danwon High is poignant and powerful. Can you tell us more about it? What motivated you to pursue it?

As you might remember from past international news reports, the Sewol Ferry sank on April 16, 2014, off the coast of Donggeochado, South Korea. From Danwon High School, 250 students and 12 teachers were on board and died in the tragedy. The classrooms of these students became spontaneous memorials and, after two years of functioning as sacred spaces, the school wanted them removed. The families of the victims protested saying they were losing their children and loved ones for a second time. They staged sit-ins, but in August 2016 an official “moving out” day was scheduled.

I got involved on the second year anniversary of the tragedy when someone close to the families asked me to photograph as much of the classrooms I could for them because rumors of an impending removal had begun circulating.

My motivation was initially preservation and progressed naturally from there.

You captured such an emotional time for these families. How did you approach them? How did you convey your intention of translating their stories into photographs?

I tried to be as sensitive as possible. My friends and contacts introduced me as an independent photographer who wanted to understand what was happening. I explained why their stories were important to me and why I was passionate to document them.

But in our actual moments of interaction, I found all the words disappeared and what remained was unspoken openness. What was said didn’t matter so much as my actions. I was cautious not to interrupt the people I was capturing. It may sound odd but I thought of myself as an elephant in the room that knew how to become invisible. When I was able to do that, I found these families would give me the gift of themselves and their experience which was loss and profound grief.

Grief is a very personal experience. Where does one draw the line between what one can photograph and what one should keep private?

Everyone has different sensibilities so that’s difficult to answer. But for me, I think the lines are drawn by a story’s intent and context. Do the images provide context to the story or not? Are they for the greater good? I feel those are necessary considerations of a responsible photographer. For example, my purpose for this essay was to explain in photographs the deep connection these families had with these classrooms. I wanted the viewer to feel like I did, a guest in a sacred place. Everything else I captured was left out.

There are plans, although not yet concrete, of moving the memorials to another place. Will you continue this series then?

I think there will be a follow up but knowing when is hard to say. During the six months that this documentary grew, I tried to imagine it as a first chapter of sorts. That mindset allowed me to create what I consider a concise, self-contained story. There are lots ideas for the next chapter, and I’m hoping that whatever form it takes, that it will grow as organically as the first.

I can’t imagine how emotionally taxing working on this photo essay is. How did you prepare for it? What is the most challenging aspect of it?

In the beginning, I wasn’t emotionally prepared at all. Being at the memorials when they existed alongside the families was overwhelming at times. But as a photographer, you’re working on a story, not just bearing witness. I knew that no matter what I felt, it could never be equal to the grief I saw.

The most challenging aspect was acknowledging all these intense emotions, but also trying to let them pass through me because I needed a clear mind to capture them.

It would be late at night, while editing, that I’d allow myself to confront what I blocked while shooting. That’s when it was okay to be swept up. That’s when the images spoke the clearest.

What are the important lessons you learned through this series?

There are two things that I keep thinking about. First, if you share real empathy for others an invitation into their world is returned, even when you’re visiting them on their worst of days. Also, that grief is a necessary and natural part of the healing process. But when grief is denied or ignored, sorrow is compounded because the healing process can’t be completed. That’s why I believe peace remains out of reach for the majority of these families.

What’s next for you?

Fortunately, quite a lot. My street photography project, Wrestling In The Streets Of Seoul, was recently on display at this year’s Photoville in NYC as an honorable mention to the 2016 Exposure Award. A different project, Reflections Inside The Seoul Metro, just received the Top 100 Award in LensCulture’s Street Photography Competition 2016. So, I’ll be hitting the streets trying to ride on that momentum.

What I’m most excited about, however, is the Magnum Workshop that I’ll be attending in Bangkok this October. The workshop is going to be taught by David Alan Harvey. I am so pleased I’ll be learning from this master photographer whose work I truly respect.

All images and information in this article are provided to Lomography by Argus Paul Estabrook and used here with permission. To see more of his work, visit his website or follow him on Facebook and Instagram.

written by Eunice Abique on 2016-10-10 #people #south-korea #argus-paul-estabrook #danwon-high-school

One Comment