The Many Names and Faces of the Diana: An Interview with John Neel

10 Share TweetThe Diana camera was a simple toy camera that became a sensation in the 60's. Known for its soft focus and Impressionist, Pictorialist results, the Diana was an artistic tool for experimental photographers. John Neel, an American fine art photographer and author of photography books, had a long history with the Diana and its many personalities as it was rebranded over and over with other names.

In this interview, John shares his experience with the original queen and makes comparisons with the Diana clones.

Hi John! Welcome to Lomography Magazine! Firstly, how's life as a photographer for 2018 so far? When was your first encounter with the original Diana?

The Diana is a charming little camera that is also blessed with some not so charming characteristics. To be honest, it’s been a while since I have picked up a Diana to take a photograph. Digital has occupied most of my creative time these days. However, there was a time when the Diana was one of many film cameras that I used in my work. I do miss the Diana. It was an important camera in my learning to see. It taught me how to look at the world. It taught me how to play with photography. I believe that the Diana was the camera that steered my work toward a more relaxed way of working with any type of camera. It certainly taught me to see the world in a more open way.

I was introduced to the Diana by my first photography teacher when an art student at the University of South Florida. That great teacher was Oscar Bailey. Signing up for his class was the beginning of my photographic journey. Not only did he introduce us to photography, he made us aware of the imaging greats — Robert Frank, Garry Winogrand, Nathan Lyons, Walker Evans, Jerry Uelsmann, Robert Rauschenberg, Bea Nettles, Betty Hahn, Diane Arbus, Sally Mann, Lee Friedlander, and the whole history of image makers who were creating important artistic work. Oscar knew many of the best. I was lucky to have Oscar as a teacher. He showed us the good stuff long before artistic photography became what it is today. Oscar taught us to be open-minded. It was the image that was important to him.

Nancy Rexroth, was one of those photographers we learned about. Her book — Iowa inspired countless photographers to take up simple cameras. Her simple camera was the Diana. Her book was recently reprinted by the University of Texas Press.

You've been incredibly familiar with the Diana clones! Which ones were your favorite, and which ones were the worst? May you share us the good and bad points of each clone?

I don’t think I can speak for all the clones that were ever made. There were way too many. I was always more interested in using them to make images than in collecting them. The original Diana was the one to use. It was the camera that had all of the abnormalities that made the camera so popular. It was my main choice. Although, I did shoot with the Debonair nearly as often.

Concerning usability, Diana and its clones were not for those looking for an easy point and shoot camera. Of all the TOY cameras that I have owned it was the Diana that I fell most in love. If any camera stands out above the Diana, it is the Debonair – only because it seemed to have a slightly better build quality. That also meant it fell a little outside of the expectations of the Diana. It was perhaps too perfect for true diehard Diana users.

Many clones were produced with only a single shutter speed or were lacking in focus capability. Some, the Diana included, had variable apertures, while others did not. The worst ones were more prone to light leaks than the Diana, all of the cameras had terrible neck straps, and crappy viewfinders. For that reason, I shot most of my work from the hip. The glue holding the chrome bezels would loosen and fall off, and the shutter on most lacked a ‘B’ setting for doing long exposures. The answer to these problems was to just not care. The only important thing was to use the parts that worked. Users ditched the lens cap, the strap, and the manual.

The Diana clones had a number of interesting and somewhat strange quirks. One of the most common was the light leaks that occurred. At the time light leaks were something I tried hard to avoid. They didn’t really interest me. Though, it was a pleasant surprise when it happened in the right context and the right subjects and in an interesting point in the frame. For me personally, the lens produced enough flair and aberration. I did not need more. I wanted to record the light that came through the lens. To me, that was the magic.

Once the camera was carefully taped, I would put it into a black plastic garbage bag along with five or six others for the day’s shooting. Once I finished shooting the 16 shots of one camera, I would reach back into the bag for another camera and continue shooting. The bag was another level of protection from light leaks. At the end of the day, the cameras would be carefully opened in the darkroom for processing.

Because of the potential for light leaks, I always loaded the 120 film in a darkened room. In order to combat leaks, black photo tape was used to seal all the edges of the camera’s back, bottom, and sides after the film was loaded. A cover was fashioned using the same kind of tape in order to cover the red film counter window located on the back. These were important precautions to ensure that light did not penetrate through the camera’s leaky “light traps” or through the red window to the film’s backing paper. Black tape was an essential part of the process of shooting the Diana.

The beauty of the Diana was in its capacity for exposure adjustment, its toylike simplicity as an imaging device, a wonderfully flawed meniscus lens, and slight quality differences from one camera to the next were all viewed as fortunate results of the limited quality control during manufacturing. For the user, those inconsistencies were part of the charm. Each camera had a different signature that added to the serendipitous images it produced. Chance was a good thing. Chance is a good lesson to learn.

Where did you get the clones? Where do they usually come from?

Most of my early Dianas were handed down, bought at garage sales, or found in old style drugstores, variety stores, or weekend bazaars. These days, your best bet is to look on eBay or maybe look for them at a camera club sale.

The original cameras were sold for only a dollar or so. Today, they are sold on eBay upwards to thirty or so to over a hundred US dollars. Prices have grown as a result of renewed interest and to a certain degree — their rarity, condition and how enamored one becomes to these cameras.

May you share us the one huge difference they have with the original Diana?

It is probably best to list a few. There were a number of differences. As I mentioned previously, most of the Diana clones were produced with even less quality control than what the Diana is known for. Many did not have the more desired controls that were part of the Diana and the Diana F – such as aperture adjustment, focusing, or a “B” setting. Having a slightly different feel and in my mind, more robust, the Debonair had a smoother, more refined body. Everything it seemed to possess a slightly higher overall quality. I don’t remember it having the same kinds of light leaks or film jams that are associated with the Diana or other clones.

Light as a feather, the Diana or the Diana F (the F stands for flash) was just rugged enough to take a certain amount of gentle abuse. All of the cameras from the Hong Kong manufacturer Great Wall were molded plastic with some metal parts such as the shutter, lens bezels, and badging. The plastic bodies of all the clones had the feel of being cheaply produced — which they were. Part of the charm is the amazement that they worked at all. Sharp images were not to be expected in the traditional sense of lens sharpness.

For you, what's so great about shooting in 120 format with a plastic camera such as the Diana?

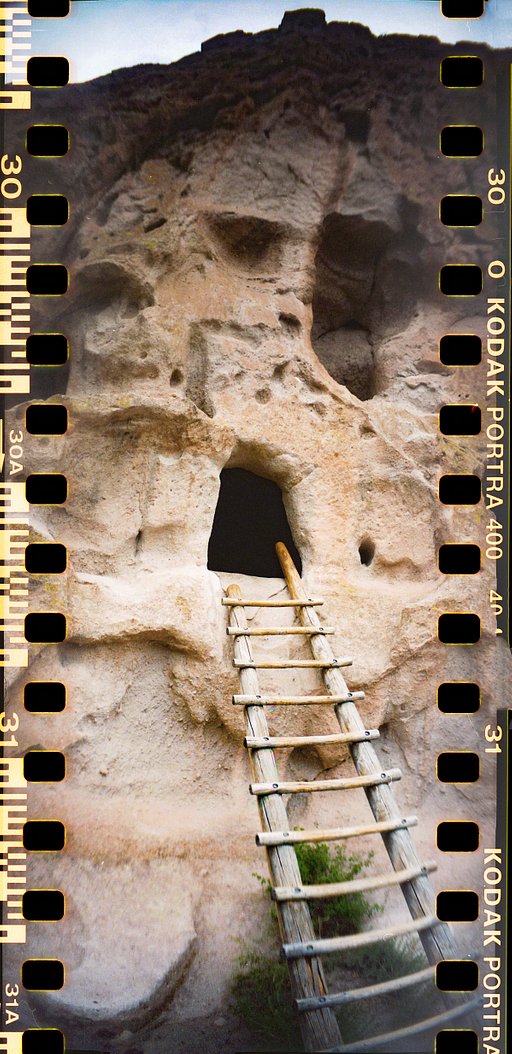

For me, it was the lens. The combination of the simple plastic optic and the 4 X 4 cm image frame produced most of the magic. To expect the same kind of image from a smaller film such as 35 mm would not have worked. The images produced were not rectangular and sprocket holes would only get in the way of the simple square frame. The scale of the negative along with the lens was in part responsible for the particular look of the final work. The image was meant to be printed as a square on small format paper.

At the time, I liked to print on an Agfa paper called Portriga Rapid. 1d23f03ba0ed. For me, it was a beautiful paper that produced a beautiful sepia tone with a very slight greenish tint. It had a pleasing contrast and what might today be called a luster like surface. It happened to be my favorite paper for all my early black and white work. It was real photo paper that used real silver to produce magical images.

The Diana and its cousins have a look and feel that makes them uniquely capable of producing dreamlike imagery. To make them any less flawed, would defeat the inherent qualities we love.

The simplicity of the entire camera is one that can allow for a very different experience for the photographer. Basically a point and pray camera, the user learns to anticipate the results. The photographer is free to simply react to the subjects with a camera that sees the world in a unique way. The images tend to present a Zen-like view of the subjects they capture. The original cameras were meant to be more of a toy or novelty item. It was a giveaway at parties. There were versions of the camera produced for restaurant chains. I remember one red one that was branded with the Shakey’s Pizza logo. Not to mention all of the variations produced for the entire world that were labeled in many languages and sold in many countries.

To whom would you recommend the Diana camera?

Like any camera, it will have a certain appeal to special kinds of camera users. Back in the day, it was used by many different image-makers, including graphic artist, designers, and fine art photographers. It had an appeal to a large number of creative artists. In more recent years, during the transition to digital, some wedding photographers were using the Diana to augment the weddings they were shooting digitally in order to provide “art images” to the wedding party.

The Diana was probably the first “experimental” camera I had ever used. By experimental, I mean that it had its own look and its own signature. It also means that I started to play with it. With the Diana, I played with multiple exposures, overlapping exposures, created stereo frames for 3d viewing, or exposed multiple frames and printing them as a single panorama image. Along with pinhole cameras, the Diana started my thinking about the concept of play as a way of working. Even today, that playfulness has become an obsession with all my work using all kinds of imaging devices. When I worked at Kodak, that playfulness with cameras like the Diana and Holga led me to a number of inventions as well as many camera concepts for digital imaging. During that time, I explored many unique cameras — both film and digital — for the purpose of creating unique imagery.

The Diana was not a snap-shooter in the same way that the Kodak Brownie, the easy to use point and shoots from other companies, or Polaroid cameras. Those types of cameras were usually loaded with films that could be dropped off at the local drugstore for processing, sent to a photo-lab or that were self-developing within the camera.

The average person was just not interested in having to load the film into a camera that produced soft images, with unpredictable light leaks, and all of the abnormalities that we Diana users adored. They were certainly not going to process the film or print them in a darkroom.

The Diana was a camera that allowed the user to respond to the subject with a sense of serendipity. It compelled the user to look at the entire world in front of them. Its simplicity encouraged the user to play. It required the photographer to see reality in new ways. The snapshots it produced had an often strange, dreamlike presence — verging on the surreal. For all its “flaws” it is an amazing tool.

The Diana was for many a serious tool for serious play. It still is.

Read John's comprehensive editorial about the Diana in Lens Garden. John is the author of Focus In Photography and Rethinking Digital Photography. They are available on Amazon, and Barnes and Noble, and scores of great bookstores worldwide. Get your own Diana F+ at the Online Shop and Gallery Stores worldwide.

2018-06-24 #gear #john-neel #diana-f-camera #diana-history

No Comments