LomoAmigo: Paul Del Rosario Shoots with the Belair

5 Share TweetPaul Del Rosario is a photographer who has been based in Japan for 24 years. Finding beauty in messy Tokyo streets , he captures the chaotic scenes in black and white. He also manages 120 love, a fashion and lifestyle brand that integrates film photography into popular urban street culture.

Hello Paul, please introduce yourself.

I’m originally from San Francisco, but Japan has been my home since 1991. I picked up photography as a teen, and it’s become an essential component in my life. I can’t imagine a day where I did not think of some aspect of photography or filmmaking, particularly 8mm, which is a new camera-lens interest of mine. I used to shoot a lot of studio portraits, but now I devote my photography to taking cityscapes.

How did you learn photography and why did you choose to shoot analog?

I took a photography course in high school, and I wanted to pursue photography professionally as a photo journalist, but I can honestly say that I was not brave enough to take this route. I had plans to go to photography school after graduation, but at the time, it just didn’t seem “realistic” enough.

At the moment, I’m being advised by Japanese photographer, Osamu Kanemura and he’s been instrumental for me on how to “not care” about photographic rules and guidelines. I’ve always been interested in unconventional things, not just in photography, but also in architecture and graphic design. So, working with someone like Kanemura who operates on a visually extreme channel has been helpful for me in exploring the abstract.

I grew up with film and have not “graduated” yet from this medium. I think once I produce something substantial and self-satisfying, that’s when I’ll know that I’ve understood film, and then I can decide from there what I want to do next.

Could you tell us about 120 LOVE?

There’s something special about medium-format film photography, and I wanted to share and celebrate this medium with others through a fashion and lifestyle brand. Fashion brands were created through activities such as sports and urban street culture; I felt photography needed representation; hence, the birth of 120 LOVE. We can still enjoy photography even without having a camera around our neck.

In Japan, people say “roku roku” to describe “6x6.” There’s this quirky feeling about the sound of “roku roku” or “six by six,” as well as how it appears visually on a t-shirt. Most people usually recognise it as a mathematical equation, but photographers will automatically know what it means and know who you are, and it’s a nice feeling when you meet people who understand this language of photography. 120 LOVE is still young, but I hope to celebrate the analog culture through this small venture.

Tell us about your photographic style and principles.

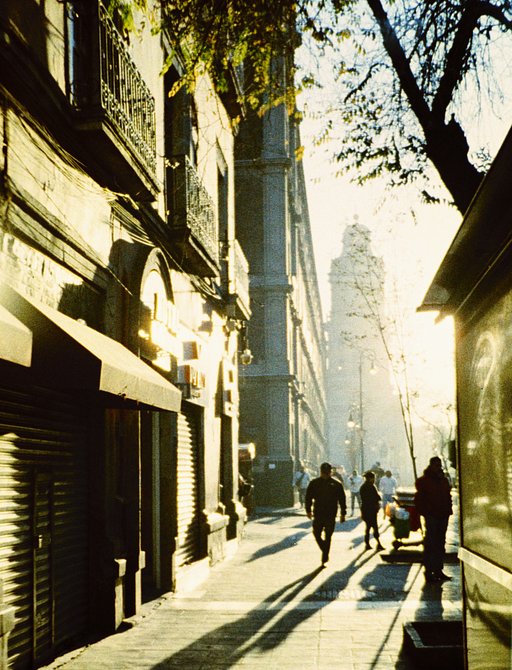

If trash were a genre, I would be in the middle of this mess with a camera. Specifically, I like taking pictures of chaotic Tokyo which one will probably not see in guide books, and goes against the grain of cliched Japan. For me, one point that I enjoy about living in Japan is the photogenic remnants of Showa Japan; tangled electrical lines colliding with urban landmarks that seem to pile on top of each other with no rhythm or regard for rules. I spent part of my childhood in Japan, so there’s this nostalgic feeling of such scenes, as well as the modern day shotengai, which still retains the funky aesthetics of the 60s and 70s.

But I don’t want to shoot Tokyo snaps for the sake of taking snaps. I want to shoot the visual distortion and weirdness of the Tokyo, and show the world what they don’t want to see.

Shooting a cityscape that is visually violent and odd goes hand-in-hand with an organic / analog workflow where “problems” are statistically higher to occur as opposed to shooting in digital. The moment you put film in the camera all the way to the final output of printing in the darkroom, there is potential room for error, but I welcome this type of workflow. Light leaks, fluctuations in temperature of processing chemicals, dust or bent negatives; these are inherent in shooting with film and an exciting part of the creative process where unexpected things can happen.

Thank you for sharing your contact prints. What do you think makes them special?

The feeling of developing film by yourself is still an amazing process even though I’ve done this for many years ever since I was a teenager. And when you finally see the images emerge from beneath the developer for the first time on a contact print, the paper acts like a mirror in that you see your skills as a photographer; every darkroom moment is a “Christmas present opening” experience. There are no “lies” that have been covered up by software or by darkroom printing techniques such as dodging and burning; the truth is before you on the contact sheet, and they can be quickly viewed, passed around, and touched. For me, I really enjoy the tactile feeling of spreading your contact prints on a table, or viewing them with a loupe, and making your review notes with a red pen, etc. We rarely see contact sheets these days, so I have this strong attachment to holding on to the past.

How was your experience shooting with the Belair camera? What do you like about it?

When I first saw Lomography’s Belair, I took special interest in the form factor; I like cameras with bellows. The Belair is light, compact, and has hidden strength. When you unravel the lens on any medium-format camera with bellows, there’s this awesome feeling of power as if you’ve just started up a classic car and ready to drive. Moreover, it’s pretty amazing that you can shoot three different formats with this camera, so it’s really packed with a lot of range.

What I personally like about the Belair is that it has enough accessories (lenses, masks) to shoot in different styles, yet simple enough that you don’t get too absorbed about the technical aspects of photography. When I tested the Belair, I simply set the focus to infinity and just adjusted two things: the aperture and position of the camera, i.e., adjust the light and compose your picture. That’s it. I don’t have to think about white balance, shutter priority, auto-focus or manual, or this and that mode; just point the camera and shoot. Do your main thing as a photographer rather than fiddling with an LCD screen.

Tell us about your Belair photos.

The photos that I took with the Belair follow the same pattern of a maximalist, “no-room-for-your-eyes-to-escape” feel which is what it’s like being in Tokyo. You don’t know where to look because there are too many things to look at. There’s no system to follow as everything just sprouts out of nowhere and enters your field of vision even if you don’t want to look at it.

The pictures that I took with the Belair capture a collision of forms and different subject matters; a cherry blossom tree sliced through by an electrical pole; the facades of buildings rudely interrupted by an advertisement for meat; greasy ventilation ducts at the front of a restaurant (which are not too appetizing for potential customers) are in full view and can’t be hidden because space in Tokyo is too tight, and that’s the beauty of all this – people will build and people will come no matter what. This is Tokyo.

I normally shoot this way on 6×7, so when I was shooting with the Belair, I had to get in tighter to clog the frame with urban mass, so this was a fun way to play with this camera.

I shot these images in Okachimachi and Asakusabashi because I just happened to be at those places, but this imagery is practically anywhere in big city Japan.

You can check out more of Paul Del Rosario’s work on Instagram, his website and on the 120 love website.

written by ciscoswank on 2015-05-11 #people #lomoamigos #belair #lomoamigo

No Comments