Scenes from the Epicenter — Minnesota’s Summer of Reckoning by Martin Blanco

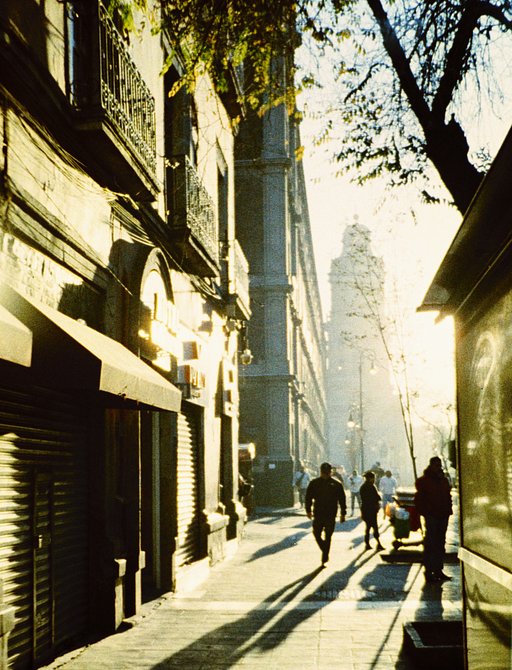

8 Share TweetOriginally based out of Brooklyn, photographer, cinematographer, and director Martin Blanco moved back to his home state of Minnesota during the pandemic. Little did he know that by the month of June, he would be out on the streets with thousands to protest alongside the Black Lives Matter Movement. A couple of years ago, he started shooting with a Canon AE-1 his friend gave him, and since then, he was hooked. Like a relic, he held on to it as much as he could until he got hooked and his passion became more of a lifestyle than anything else. With some Lomography Color Negative 100 ISO, he shot his series "Scenes from the Epicenter" that portray the protests from the heart of Minnesota, focusing on both what this meant to his city and the nation's history, as well as reevaluating his own place in society as a Latinx man. We talked to him about his passion for film, especially when it intersects with identity and activism like it does in "Scenes from the Epicenter."

Hello Martin, it's great to have you here at Lomography. First of all, can you tell us why do you still shoot film?

I really value the process of shooting on film because it invites me to be very mindful of every photo I take. Back in college, when I first started shooting, I was living paycheck-to-paycheck, and the costs of new rolls and their processing always competed with basic necessities like food or transport. I even used to have a running joke about being cheap and never shooting a photo of the same thing twice, making each exposure count for something new. And to be honest, I think that stuck! I’m a lot more lenient now, but yeah, it’s the same for the most part. Aside from that, I think there’s an inherently nostalgic process of revision when it comes to shooting film: first, you take the photo, which you then forget as it sits in your roll until, after it’s developed, you finally see its true form. Then, that image is translated into a digital scan, which is later edited and refined, and finally published. That’s four different opportunities to interact with and shape that first vision you had, and by the time you reach the end, the image has the vibrancy of a warm, distant memory.

Where do you draw inspiration from?

Both in scripted film and photography, my inspiration often originates in questions of identity, memory, and context, as well as how these ideas collide to define our present selves. As a first-generation Venezuelan-immigrant-turned-American-citizen, I am constantly in a restless state of duality, working to discover and define who I am between and beyond these two cultures. With photography, that investigation tends to be even more introspective and personal, treating my approach almost like a diary that makes sense only when studied retrospectively, informing not only the literal memories that inspired the photographs in the first place, but also that momentary, visceral impulse to preserve or even re-contextualize the present through the perspective of the lens. Keeping all of this in mind, I’m really inspired by photographers who achieve a certain degree of visceral magic within the documentary, including but not limited to Alex Webb and Rebecca Norris Webb, Ernst Haas, Fabiola Ferrero, Maya Beano, Taras Bychko, and more.

Can you tell us more about the series you shot “Scenes from the Epicenter”?

Scenes from the Epicenter is a personal perspective into Minneapolis, Minnesota's reckoning with racism, injustice, and privilege, painting a picture of a city that’s been stripped of its decades-old Little-House-on-the-Prairie facade, and instead of revealing the collective grief and outrage against the ever-present duality of white vs. black Minnesota, one punctuated sharply by federally-endorsed police murder and brutality. I returned to Minneapolis a few weeks before Memorial Day of this year, and after the tragic murder of George Floyd, I joined several demonstrations with some close friends. We gathered alongside hundreds at the George Floyd Memorial on East 38th and Chicago Ave, listening to empowering speakers demand justice for their community and warn against the looming threat of insurgent white supremacists. We marched alongside thousands through the streets and bridges of Downtown Minneapolis, reaching the infamous I-35W S bridge and kneeling down for a moment of silence only to be charged at moments later by a large gas tanker that had somehow slipped past the police barricade closing off the highway. We walked through the ruins of burned buildings and businesses in Midtown, observing the scars of outrage left behind by decades of systemic and racist abuse and terror. Above all, we witnessed a community united in a call for change, coming together every day to clean up the destruction, to donate food and medical supplies to low-income families and protesters caught in the crossfire, and to protest peacefully by the thousands in determination to commit politicians to change and embrace justice.

Beyond these moments of solidarity, this series is also a personal confrontation with my own privilege as a Latinx man who grew up in the suburbs of Minneapolis, for the most part slipping under the radar and easily assimilating to the prevalent white culture. The communal vibrance of the protests was always contrasted by an air of dread, widespread fear of the gathering shifting violently in an instant at the hands of nationalist terrorists. A fear that did not fade away, and instead magnified as I returned to my family’s town in the evenings and the diversity in population dwindled to a minimal. It felt like a separate world, where mostly white middle-class families trekked down to the lakes and lounged on their boats while a mere car ride away buildings burned and thousands cried out in outrage and demanded justice and the basic human right to life and equality. As the movement spread across the country and the federal response grew exponentially more fascist, neighbors’ apathetic and dodgy outlooks to the situation felt increasingly more hostile, especially in rural Minnesota, where conservative sentiments remain the norm. The soft amber color of my skin burned proudly and fearfully against the closed doors and shuttered windows of my family’s neighborhood.

Once and for all, the home had lost its veil of safety. At the peak of my fear and in response to the police’s weaponizing of protester tracking data, I became attuned to the intimacy of my photography on Instagram. I had broadcast several protests that I had attended as well as shared written perspectives as a Venezuelan-immigrant who had once before lived under a fascist regime. Alongside them, the images of my family, my friends, our homes, and all of the personal and geographic metadata associated with them began to feel only like a point of vulnerability against increasing threats of paramilitaries and domestic terrorists. I remember specifically thinking about The Long Goodbye, a short film starring Riz Ahmed, where a lively afternoon in his Pakistani family’s London home is terrorized by armed white nationalists who suddenly appear in unmarked vans. White neighbors and police look the other way as the terrorists drag the family from the home, executing them one by one on the driveway. In Minnesota, after the state’s perpetuation of injustice following an amply-documented police execution in broad daylight; after the First Amendment rights to assembly and the press were disregarded and peaceful civilians were increasingly being beaten, gassed, and unlawfully arrested; and after an illegitimate, authoritarian president proclaimed himself “President of Law and Order,” the possibility of immigrant-hating, armed nationalists storming my Latinx family’s home seemed anything but unlikely. And so, within moments, I deleted the outreach platform of thousands that I had cultivated for years. I gave in to the very fear I had sworn to fight, ultimately enabling the very culture that was working to shut me down. In the wake of it all, Scenes from the Epicenter stands as a testament of Minneapolis and my own commitment to rebuild and charge racism and injustice head-on. It is a strive to never bow in fear to a systemically and forcefully oppressive regime and to stand tall against the false promises of the political elite until the demands of the people are fully realized.

Though all process of growth and development takes time, it is through collective perseverance, vulnerability, and radical love, that we will manifest real and resounding change, uplifting Black and minority communities and ultimately benefiting us all.

Why did you decide to shoot this series on film?

I knew I wanted to treat these gatherings with the utmost respect and care that I give to the rest of my work, and so film became the clear choice.

I shot the majority of these photographs with Lomography Color Negative 100 ISO film, which proved astute and flexible against the blaring sunlight of late May and early June. The slow film speed paired eloquently with my wide-open 50mm lens, allowing for various planes of focus and resulting in immersive images that feel like a viewer inside the action. A minor few, particularly the scenes at the George Floyd Memorial, were shot on Kodak Portra 800 that was pulled -1 stop, which resulted in communal scenes that have a bright, but soft contrast, speaking to the tender quality of the grief and the pain shared by many.

What pushed you to shoot the events?

As I mentioned in my earlier answer, following the death of George Floyd, there was a palpable sense of denial in my family’s town, which was only about forty minutes from the Twin Cities. People were so eager to dive headfirst into summer that they failed to recognize the blatant atrocities committed by the police, who citizens are literally paying to protect them in the first place and who are enabled by an equally negligent and supremacist government. So it was a combination of pain and outrage at it all, and just a general repulse and restlessness.

From the pictures you took, do you have a favorite one? Can you tell us the story behind it?

I think my favorite pair of images is the one of the crowd in front of the Speedway at the George Floyd Memorial versus the remains of a Midtown store. There is a conversation between the two forms of grieving that underlines the general spirit of the Twin Cities during the early demonstrations and beyond.

To follow more of Martin's work, head over to his website and his Instagram .

written by tamarasaade on 2020-09-07 #news #people

No Comments