The Side We Don't See: In Conversation with Carl-Mikael Ström

1 3 Share TweetIf you see a picture of an apple, you will define it as an apple, but that’s because you’ve been taught that it is an apple. But ... if I were to ask you, is the apple whole? If it’s photographed from the front, how do you know someone hasn’t taken a bite on the other side, the side we don’t see?

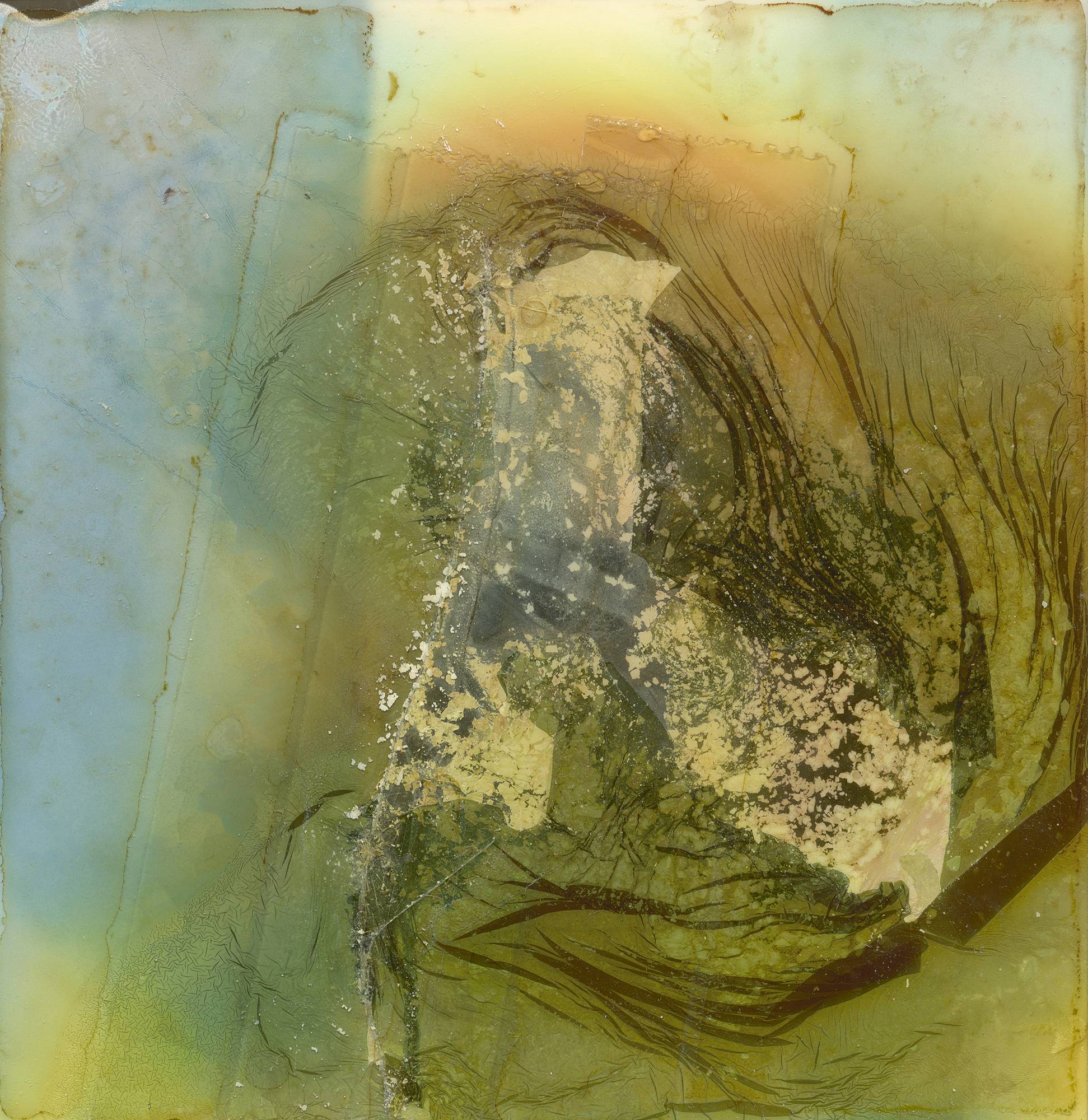

Carl-Mikael Ström doesn't call himself an artist, or a photographer, or a filmmaker. He is a montör (meaning someone who assembles). His first project, a monograph titled Montöristen, emerged from grappling with the reality of becoming a father; the failures and realities of the quotidian. In Brightness Hiding (The Failure..., his next project, which is on its way to becoming a book, his quest is for imagery beyond language.

In this interview, we spoke with Carl-Mikael about the origins of these projects, the way to the truth inside an image, and the importance of patience.

Hi Carl-Mikael! Could you start by telling us a bit about yourself and how you got started with analogue photography?

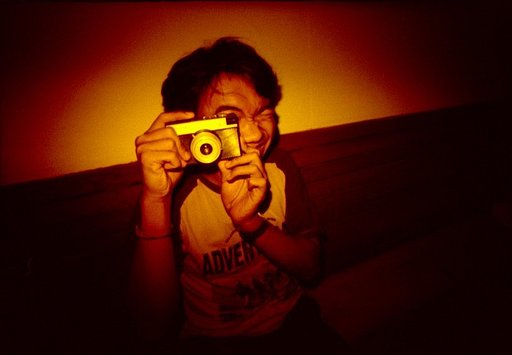

Absolutely. My name is Carl-Mikael Ström, I’m 37 years old, I currently reside in the south of Sweden, in Malmö. The earliest memory I have with photography is, I guess, like many others’ - I used my mother’s old camera when I was around six or seven years old. We actually lived in the countryside when I was growing up, on a horse farm. And a few years ago, when I was working on my book Montöristen, my first monograph, my mother found a film roll with my name on it, that I [had] apparently photographed. I have no memory of this, but now there is one picture in the book of horses running across a field. The film had not been processed, it had just been laying around for, I guess, 20 years or so. So I just developed it [by chance] and it was beautiful. It had [aged] with time, it was cracked, you know… everything was faulty with that film, there were not many pictures that were [usable] in that sense.

My first contact with a darkroom was in seventh grade, I was already back then skipping a lot of school! You could borrow a camera from the school, and you got some black and white film. I remember when my art teacher at that time helped me develop my first print, and I have a very strong memory [of this] - you expose paper to some light and you put it into the developer and you have a picture! And from that moment...that stuck with me.

During my teenage years I always made pictures, but I never thought about being an artist, a photographer. I wanted to be a musician. That’s what I wanted to be for many, many years. And when I was twenty-one or twenty-two, I realised, I’m not going to [make a living] on this, I want to do something else. So I came back to film, art, photography, and started taking it more seriously. I had a lot of friends that were professional musicians, so I started hanging around with them, doing short documentaries and music videos and things like that. So it’s been a very [varied] trajectory of things.

You said in an interview that you don't like to identify yourself as an artist, or a photographer, or a filmmaker. Why not?

Well, first of all, I think there’s so many brilliant people that really are photographers out there. There are many people that I respect. For example, I assisted the Swedish photographer JH Engström for many years. For me he’s really a photographer. Because he makes great photographs. But [of course] it’s very individual, how you define a great photograph.

When I created my first monograph Montöristen, it was a play on words - it’s from the Swedish word montör, [meaning] someone who assembles. Because I don’t like the idea that a title defines who you are. I think it’s very boring when people ask you, if [you] meet for the first time, “what do you work with?” As soon as I get this question I usually lie. People get scared when you ask, “who are you, what do you do?” Because we have this idea that we need to define ourselves so much [with a] label. I could call myself an artist but I don’t find it a necessity. I don’t find it [necessary] to call myself a photographer, or a filmmaker, or a writer, or a poet. Because there’s also so many connotations that come with those titles. And I guess calling myself someone who assembles, personally that is more true, more honest.

Did you start working with lots of different media because you already had this attitude of wanting to reject specific labels? Or was it the other way around - you were already working with a variety of media and doing what you wanted, then decided that a montör is what best defines you?

I don’t think there is a very straight answer to that. I believe that society, as it [appears] in school, etcetera - the whole idea is that you’re supposed to become something. But you’re not supposed to become yourself. You’re supposed to become an engineer, doctor, musician, artist, whatever. But there’s always a label. I think my way of functioning, of responding to this world with my sensibilities, is that - I’m trying to make sense of something. No matter what it is.

There aren’t that many actual raw images in your projects. What kind of techniques or materials do you use to manipulate your images, and why do you feel that those techniques make an image more honest?

I usually say I use any means necessary to get the image to say what it really wants to say. It’s a gut feeling. I don’t reuse the same technique often. I get bored with it quickly. I don’t really have any recipes, but also, I can’t lie, some people are very fortunate and have the finances to do whatever they want, all the time. That has not been the case for me. So, by all means necessary. If I have a laser printer, that’s what I will use to print my pictures. If I have a canvas and gesso primer, I might do transfers. If I have paint and only negatives, I paint on the negatives. If I have a chemical or a cleaning product or whatever, I might use that on the film.

For me, while in the process of doing something, I don’t judge it [in that moment]. Because over the years I’ve learned - JH Engström was the one to tell me this - that time is the most essential tool. You do several photographs, you develop them immediately, you look at them, and you choose some images. The selection you make today will be very related to all your previous experiences and where you are right now. You don’t necessarily see what it is you want to express. You choose the obvious images, that’s the best way for me to explain it.

No matter what kind of techniques you’re aiming to use, it’s not really important, because - for me, at least - you really need to find what the image wants you to tell. The truth inside the image. And [it’s important] that you live with your work, because you need to keep it visible for yourself, and accessible. All my kitchen cupboards are just filled with boxes of prints and paint. There is one drawer for cutlery and kitchen knives. Having accessibility to these things, I think, will eventually unlock new solutions or techniques. But techniques per se don’t matter for me, because it’s not about the technique, it’s about the image. The technique is just a means to get where you want to go.

So for you, the raw image, or the negative, is really just a blank canvas, or a puzzle that you have to figure out. Rather than seeking something particular to photograph, do you photograph quite randomly and then think about what to do with it later?

Yeah, mostly. Of course there are situations, like if I photograph objects, [then] I guess you could call it “staged”. But otherwise, no. I’ve also used so many [random] techniques, like [using] my cell phone and then [printing] that on film. We have so many options right now. When I was a kid I really wanted a video camera, but I couldn’t afford one. And now, when I see my own son, he’s 7 years old, I [realise] it’s really interesting [to] have the means to do so much with so little. I’m not going to say it’s great, because I also think it can be a hindrance. I think it can hinder you, that you have all these options all the time. I think limitations are good. Self-imposed limitations on how to approach the reality of what you want to say. But who knows. . . what I say today will be something different if you ask me tomorrow. I would give a very different answer.

It's interesting that you talk a lot about the importance of limitations, but also the importance of full accessibility and visibility, because your latest project Brightness Hiding (The Failure… was about reckoning with the idea of photography as a language, right? Dealing with the fact that there are all of these limitations when you create something, and yet there's still no control over how the viewer sees or interprets that. Do you think you could tell us a bit more about the origin of that project?

Absolutely. The project [title] really comes from a quotation from the Austrian philosopher, Ludwig Wittgenstein, from his book Tractatus, which was published in [1921]. There is a quote in there, the English translation is: “what can be shown cannot be said.” I’ve always read a lot of philosophy, but that quote really stayed with me and I started thinking. This book is mostly about [the question], what is language? What is definable? For me, at least - that's the way I interpreted it. But the idea of the project was that I wanted to create images that existed outside language. I still haven’t found a solution to that. What is outside language exists outside the borderlines of what we can see and how we interpret the factual reality that we are in.

A simple example - if you see a picture of an apple, you will define it as an apple, but that’s because you know it’s an apple, you’ve been taught that it is an apple. But then it comes down to the question - if I were to ask you, is the apple whole? If it’s photographed from the front, how do you know someone hasn’t taken a bite on the other side, the side we don’t see? Maybe it’s a bad explanation, but I came to see the [project] as more of a ladder, of getting to the possibility of experiencing something internally that we cannot explain.

On your website, in the introduction to this project, you wrote that everyone projects their own experiences onto the images they see, so the original image becomes distorted. I was wondering, then, if we try to reject that idea of individual interpretation, there must be something else, something universal at the core. Do you think that there's some kind of objective truth to every image, however abstract that might be?

Maybe on an individual level, but it’s not something that is reachable, I believe. I think the whole point is that - you can have every intention when you make an artwork. That [the piece] is about this [or that]. But as soon as you put it out there, you don’t have that authority over the work anymore. Of course, if we’re in the same cultural context, we might find connotations that are similar. And of course if we start by reading the image and identifying the objects that we see - let’s take the apple as an example again - if you and I are standing in a gallery together looking at a picture of an apple, it’s highly likely that we’ll agree that it is an apple. A person might come and say, that’s not an apple, that’s a pear. So no, I don’t think there’s an objective truth to it. It’s a very difficult question, but I like it, it makes me think.

Maybe there's not an objective truth but there is [some kind of] truth to it - it’s difficult … Because even if you’re looking at an abstract painting, you’re going to say, ok, there’s green, blue, red. Brushstrokes going this way, that way. I think the closest thing you can do is, I don’t know, take a tab of LSD. Maybe a psychedelic experience is the closest you can get! I guess I just like this idea, that there is a possibility. And also [the idea] that failure is such a great teacher. You need to be brave and you need to fail a lot, to just live in this universe. [Make] mistakes, many mistakes!

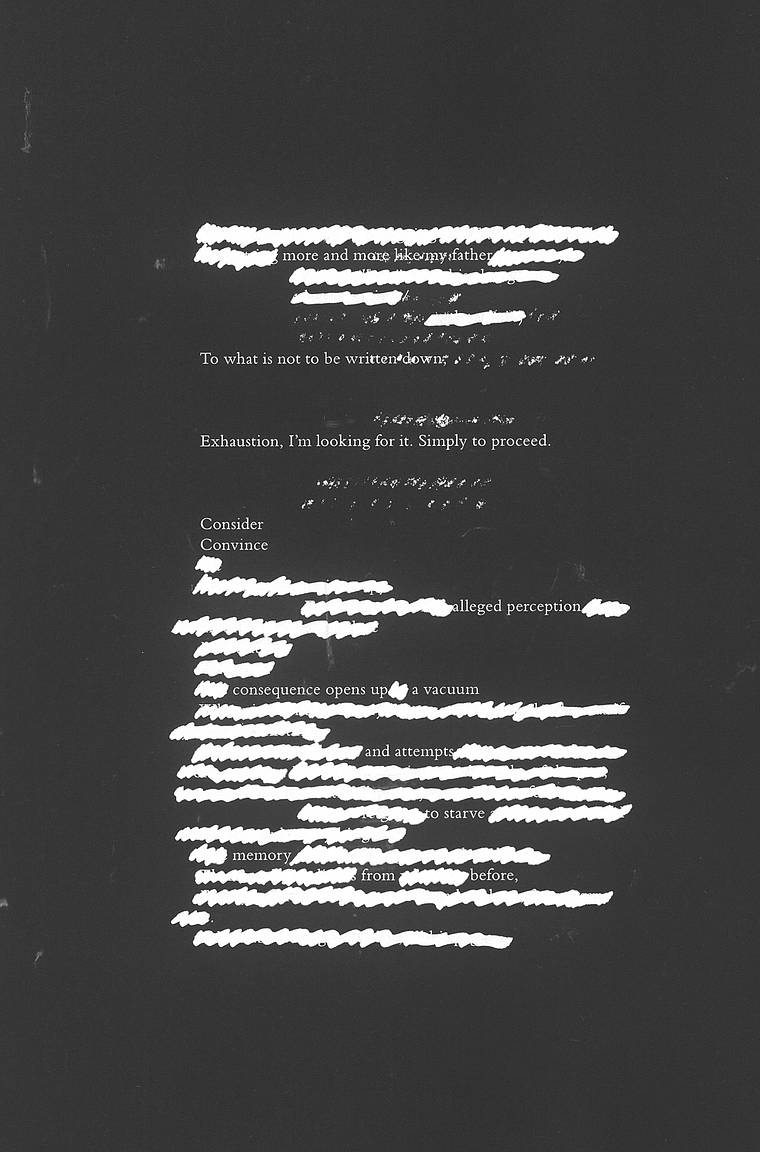

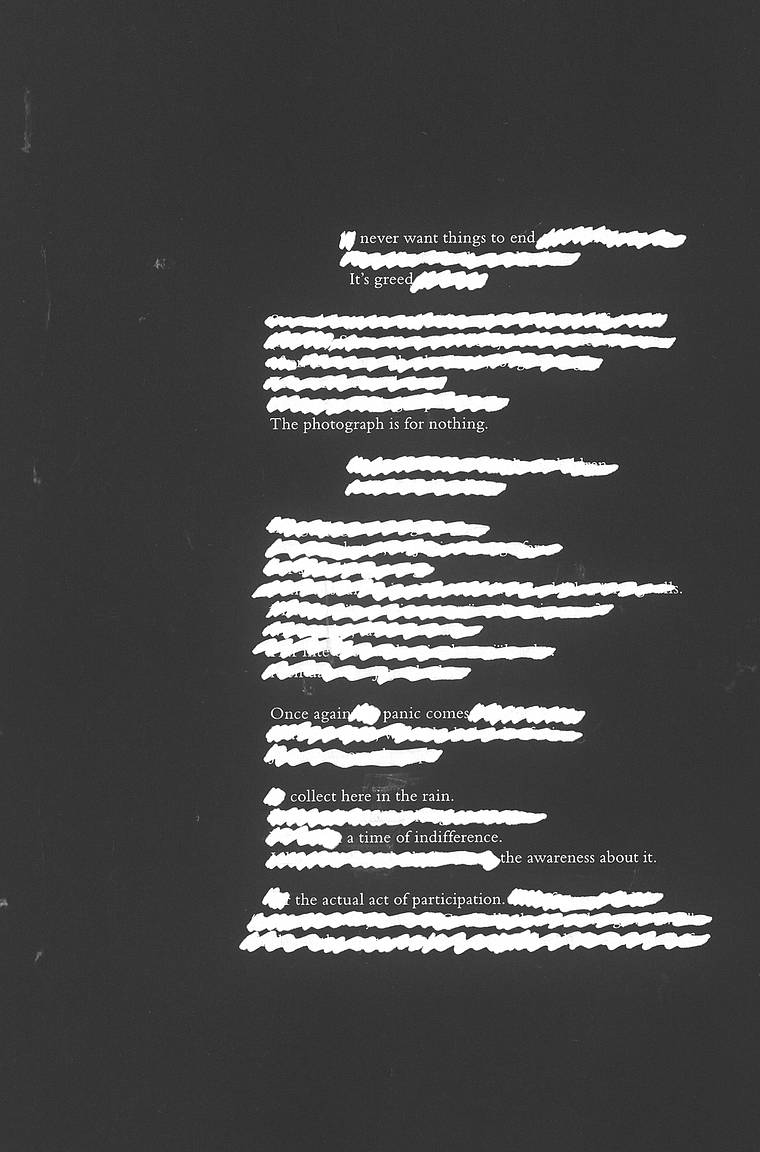

This project came just a few years after your first project, Montöristen, which emerged from the birth of your son. The premise of rejecting language and seeing things without being able to express them, it’s very reminiscent of the way a child or a baby sees the world. In the book you even have pages of text that is mostly blacked out - that reminds me of the way a child might hear something but only pick out and understand certain words. Is that something you thought about?

When you say it, it makes absolute sense, but no, I hadn’t thought about that! But you are completely right. So, that’s very beautiful. I will steal that quote from you! I guess subconsciously, yes. It’s a funny story, actually. The text for Montöristen, from the diary entries, was between 1500 and 1800 pages [long]. I was writing frantically at that time after [my son] was born. I had a very hard time [comprehending it], and I was also still very young. I was 29 when my son was born. And the relationship with his mother didn’t work. We stuck together for a while more but it was a very difficult period.

I was in Lisbon together with João Linneu from Void, my publisher, and we were working on the final maquette. I had made a rough selection, because the idea [at] first was just to publish all the texts, but I couldn’t afford translation, editing. . . we had limited funds and not enough time. I think that was good [though], because otherwise it would have been completely incomprehensible. But I was sitting there in this small flat in Lisbon, and in the middle of the night I had this draft of the text [in front of me] and it was so stressful - so I just took a black marker and started blocking out text. Thirty minutes later or something like that, João asked me, how is it going? I said, “I’m finished, let’s do it now.” So then I just scanned everything quickly and we finished it!

Later, when I came home to Sweden, I started doubting the text, because there were misspellings, and so many things that absolutely didn’t make sense. So I tried to redo it, and, my God, it became so bad! So I was like, ok, I’ll leave it as it is, this was meant to be. But yeah, the way I want text and image to work together. . . I’d like it to work seamlessly. I think visually, I achieved that in that book. But then if you judge the text as a literary work, it’s terrible. It’s absolutely terrible! But there’s some quality to that too, you know. There’s a quality to terrible things. There’s one page where everything else is blocked out except “have patience”. And, you know, that’s cliché, that’s preach poetry, but it’s also true! Sorry to say, but cliché things are often true, often very brilliant.

I’m also trying to de-dramatise the whole Brightness Hiding (The Failure… project now because I don’t want you to have to read fifty pages or a long project description to understand the project. I want it to be inclusive, I don’t think you should need any background knowledge when you [approach] an artwork. So now I’m thinking of scrapping all text in the next book, or have it separate or something, I don’t know, I haven’t found a solution yet.

How did you go about creating something new, like embarking on this next big project Brightness Hiding (The Failure… after Montöristen was done?

Well, for me, I’ve always worked in phases. I have some artist friends who work all the time, just produce, produce, produce - and I try not to look at what they do because it stresses me out! After Montöristen was done, I was travelling a bit and I was in Athens when the idea came to me. When the book was finished, I was already thinking about something else to do, because of course there were a lot of rejected pictures, a lot of material just lying around. But there will always be a phase of collecting - I don’t necessarily produce so much, maybe I read a lot. I do something, just not photography. I draw inspiration from other things.

Then there will be a phase of producing a lot - I feel it coming now we’re in the fall. At the moment my kitchen table is full of all the chapters of Brightness Hiding (The Failure… It’s 12 [volumes] at the moment, which is such a huge project. So now I’m in the editing and selecting phase and at the same time I’m also writing a lot of ideas, creating things next to it. I wish maybe one day to have a more [structured process] but right now it’s more or less like the seasons. It comes and goes in waves.

From September last year until mid-February I did so much work. I didn’t sleep a lot at all. And then, of course, when you don’t sleep a lot, eventually you burn out. So from mid-February I [realised], I need to rest. But now when I look back at everything I did - there are thousands of pictures, prints, sketches - so now it’s very nice, because there’s been [enough] time in between to start working with it again. Once again we come back to time - I have a bag where I put all my film, then I develop it when the bag is full. I don’t like to develop too early because then you start thinking. When you have an idea I think it’s more important to leave it. I actually have a brilliant example of that! I also do a lot of films - a few years ago, Lomography did this LomoKino, very fantastic. I did a lot with that, and I remember the joy of developing those films several months later, probably a year later. And it was at a lab in Paris where I actually got scanned [video] files that I could look at immediately - because I didn’t want to scan those frame by frame! That was beautiful. So I think it’s very nice to leave it for a bit, let it brew and be patient about it.

Do you think taking that time also helps you, not only to not be too attached to the moment of the image, but also to see it as a blank canvas, something to bring the truth out of?

Yeah, I think your judgement is often clouded with the immediacy of things. [Say] you meet someone and you fall in love, for example. You’re not a rational human being in that period, you’re not! Not even physiologically. You’re stupid, and it’s wonderful! But for six months to a year, you’re like this. So of course, when you’re in that period and you photograph and select images and you look at them - it’s very obvious what you’re going to choose now. You’re not going to choose a picture that depicts the person you’re in love with as a horrible human being.

What is interesting about photography as well, and one of the biggest troubles I have with it - is that you’re always dealing with the past. No matter if you develop the film the same day. It’s still the past you’re dealing with, it’s just a fleeting moment. It is something that has happened. Of course, it’s the same with a painting, it’s just not as obvious. But with photography it’s really obvious that time is passing.

Coming back to what you asked earlier about if [I have] a planned way of photographing - well, photography is both extremely difficult and very very simple. If you really break it down to what you’re doing, you’re pressing a button. You press a button - especially with smartphones, you’re just pressing something, then you get something [out of it]. But the difficulty comes down to choosing, and putting your work together and making sense of it. That’s what’s difficult. Anyone can learn the technical way of shooting or lighting, but the hard thing is selecting and putting something together, making it your own - not having someone else do it for you, but actually doing the work.

Do you think you have to be a little bit cynical to be able to do that kind of curation process you’re describing? Or at least mistrustful of the way you were attached to the image when you took it?

Yeah, you have to be very, very cynical. You have to be ruthless with it! The maquettes of [the book] Brightness Hiding (The Failure… were completely different from the exhibition of it in Helsinki. An exhibition is a completely different translation. The books consist of 1500 or 1600 images, scattered over pages, with paintings, with text. When I did those maquettes I set up rules. For example, I bought this huge A3 Leuchtturm or Moleskine with blank pages. I had very small test prints and I thought, I’m just going to see what happens. One of the ground rules was, when I put a picture down, I couldn’t move it. I could not start a new spread until I’d finished that spread. When I’d finished that spread I was not allowed to look back at it. I was not allowed to do it in a linear way. I was not allowed to look back at anything until the whole book was full. So, of course, that created some things that were really really good, some things that were really really terrible, and a lot of things in between. And that was several books.

So, yes, you have to be ruthless in the process, but I also [allowed] myself liberties since the word failure is in [the title of] the book. So I wanted to allow it to be a failure, I wanted to show my failures. I didn’t want to hide the bad images, I didn’t want to hide the bad spreads, I wanted to show something that was honestly made.

There is a sense, first in Montöristen, where there is a reflection of the failures or reality of daily life - it’s made of imperfect images and not quite coherent text. Here, again, you’re talking about wanting to show something very genuine, almost like a sketchbook. The parallel makes me wonder, is that something you deliberately want to say with your work? Or does that naturally emerge?

I think that it’s. . . maybe not constantly changing, but changing often. Because, yeah, I’ve tried doing more documentary projects and I’ve photographed people in the street, etcetera. And, not to sound egocentric or narcissistic but I have a lot of compassion - and I can’t do that. There are so many people who are great at that, and I’m just not one of them. And I’m fine with that. I’d rather talk with homeless people than photograph them. I don’t feel the need to try to tell their story, I just don’t think that’s my place.

And I think it’s very important to say, especially nowadays with social media - oh God, now I sound like a boomer! But it’s very important that we talk about the fact that life is not always beautiful! Life is also boring, life is also dull, there are a lot of people who are depressed, or struggling - and I think the compassionate thing to do as a human being is being aware that sharing your troubles can help others.

Many years ago, I also tried to reject my creativity - or I think I didn’t believe in myself. But now I’m old enough to know that it’s not a choice! It’s something I have to do to be happy, or at least more or less content, with reality. It’s something I have to do, otherwise I’m very sad. But even if I know that, it still comes back to, you know - you get depressed, and you know what makes you happy but you are unable to do that. Also when you become a parent, you want [the best for] your child as well, but at the same time you also want [the best for] yourself. There is an interesting [tension] there, [about] how you manage that.

Right now it feels like I’m living four different lives. I have a life with my son, and my fiancée is still living in Paris, going back and forth… [so] I have a life with [my son], a life with him and her, a life with her, and a life with myself. The only regularity I have is the schedule for my son, of course, because kids need stability. And on top of that, I’m going to an office job, which. . . I don’t like. I guess we all do that, don’t we? In our existence, what we experience and what we experience with others, and internally - I think it’s really important to [recognise] the gut feeling [you get] when you’re chasing something, or when you look at something and you - it’s very strange - you just think, this is good! And other things you reject and say, this is bad. There’s no good explanation for that really, how those decisions come into play.

One final question - do you have any other projects coming up aside from this new book?

Well, hopefully an exhibition next year! I'm not going to say anything more because nothing is settled. And then the last few months have been a lot about getting into composing music again, and trying to see what can become of that. I found it very liberating because I've always played guitar and now I use electronic instruments that I got recommended by a friend, who is a musician and thought I should try it. I was very reluctant at the beginning because - I love all kinds of music, I really do, but I've never played piano, or keys. But now I'm sitting here with different electronic instruments and creating soundscapes, and I'm really, really excited about that. It's very difficult, but the most important thing is that I find it fun. I can do it for hours, which I haven't felt for a long long time. So I'm very excited about that. So, who knows, maybe an exhibition with music or sounds. . . but let's see what comes of it!

We'd like to thank Carl-Mikael for sharing his work and insights with us! To view more of his work, follow him on Instagram and check out his website.

written by emiliee on 2023-12-27 #people #in-depth #language #interview #sweden #time #experimentation #alternative-process #scandinavia #identity

One Comment